Last week, we attended the Texas Lyceum’s conference, “Sustainability of Texas Communities,” in Amarillo. Thanks to Lyceum President Sarah Jackson and conference co-chairs Kristina Butts, Josh Winegarner and Nathaniel Wright for the opportunity to set the stage at the conference as the organization’s official data partner. Here are some key facts about the Texas Panhandle.

Let’s start with the Texas Panhandle and its size.

Let’s start with the Texas Panhandle and its size.

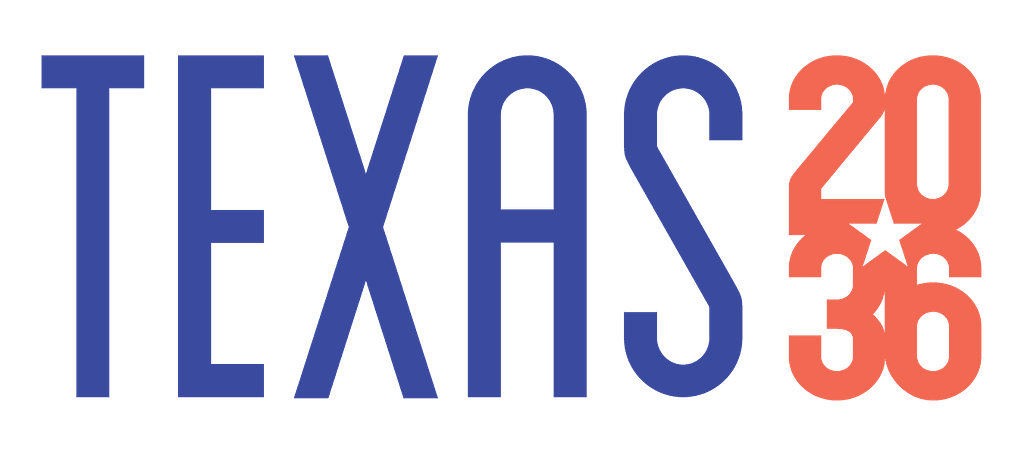

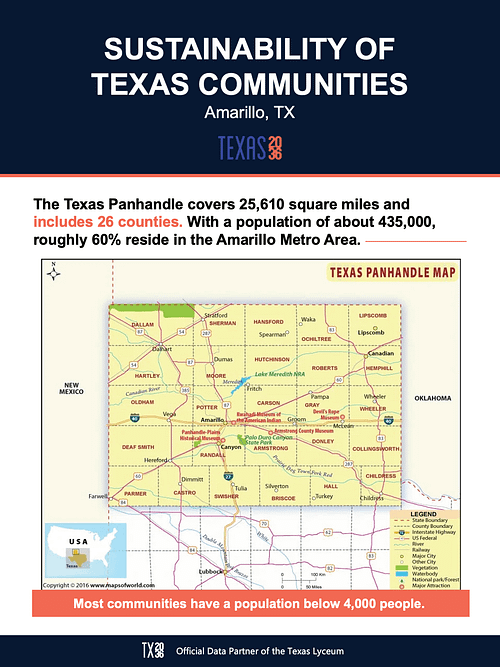

Slightly larger than the state of West Virginia, the nearly 26,000-square-mile Panhandle includes the northernmost 26 counties of the state, and borders New Mexico on the west and Oklahoma on the north and east.

With a population of around 435,000, about 60% of folks in the Panhandle reside in the centrally located Amarillo Metro Area, while most other communities have a population below 4,000 people.

The Panhandle is a product of the Compromise of 1850 following the Mexican War, which resolved the state’s dispute of territorial claims with New Mexico. The 26 Panhandle counties were officially declared in 1876 by the Texas legislature.

The Panhandle, also referred to as the High Plains, is part of the Great Plains that extends throughout the Central United States.

You may also hear the area referred to as Llano Estacado (La-now Eh-stuh–kaa-dow), which is thought to mean “staked” or “palisaded” plains.

The area is a vast, mostly flat, grassland.

However, the eastern part of the side, known as the Rolling Plains, is not as flat and has more brush given its additional rainfall. The Panhandle is also home to Palo Duro Canyon and Caprock Canyons State Parks. These deep canyons carved by rivers split the western and eastern parts.

And the semi-arid region is prime for animals dependent on grasses and built to live where water is less common, including the once almost extinct bison, prairie dogs, rattlesnakes and the tiny Palo Duro mouse.

But not all inhabitants can manage with such little water.

Lying under multiple states, beneath the Great Plains, the Ogallala (oh-guh-LAH-lah) Aquifer is one of the world’s largest aquifers expanding an area of approximately 174,000 square miles.

Lying under multiple states, beneath the Great Plains, the Ogallala (oh-guh-LAH-lah) Aquifer is one of the world’s largest aquifers expanding an area of approximately 174,000 square miles.

As the primary water source for millions of people, in the Panhandle, it’s the area’s most valuable water resource.

According to Texas Parks & Wildlife, nearly all—97%—of this area’s water needs are dependent upon the aquifer. And approximately 90% of the water demand is for irrigation of which agriculture in Texas and thus the nation depend.

But the aquifer is at risk from increasing drought conditions and water being pumped faster than it can recharge. At current rates of usage, the Ogallala may see a 70% decrease in water levels by 2080.

The Ogallala’s depletion plays a persistent challenge for the Texas Panhandle’s economy.

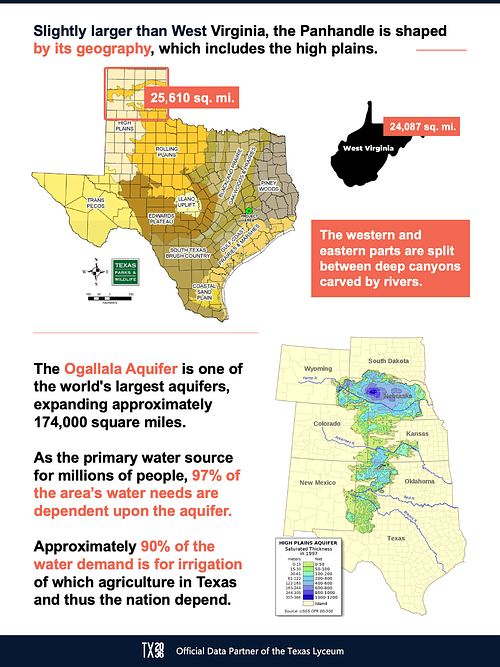

Starting with the region’s rich ranching heritage, the Panhandle’s economy has primarily been bound to agriculture, energy and the defense industry:

The Panhandle remains a top producer of fed beef, cotton and sorghum, as well as dairy, corn and wheat.

Yesteryear’s oil boom of the 1920s and 1930s is coupled with today’s energy expansion of renewables. In 2000, there were no wind turbines in the Panhandle, but that number shot up to about 2,400 in 2021.

And the defense industry has been one of the main sources of skilled and well-paying jobs in the Panhandle, driving in talent from outside of the region for a specialized skillset required.

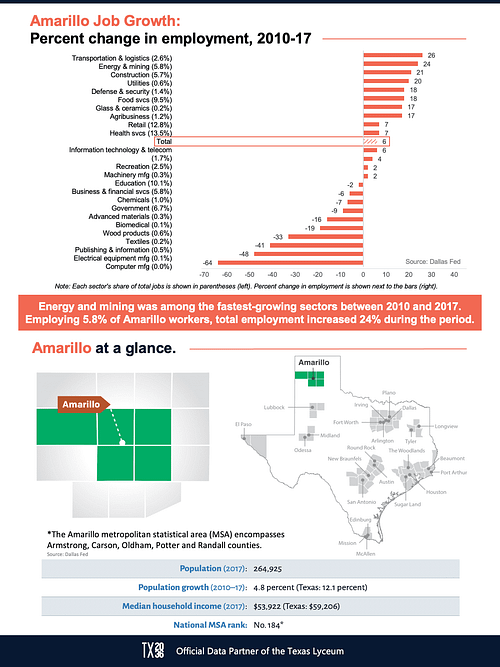

Specific to the Amarillo metro area, as you can also see on your handouts, the defense and security sector grew rapidly with an18% change in employment from 2010 to 2017. Likewise, energy and mining was among the fastest-growing sectors for Amarillo in that period with an employment increase of 24%.

Specific to the Amarillo metro area, as you can also see on your handouts, the defense and security sector grew rapidly with an18% change in employment from 2010 to 2017. Likewise, energy and mining was among the fastest-growing sectors for Amarillo in that period with an employment increase of 24%.

But the region is growing in parts. For example, Randall, where Amarillo extends into, is projected to see 100,000 more people by 2050.

With these changes in growth also come changes in the people who call the area home.

Here’s a breakdown of the largest concentration of folks in the Panhandle by race/ethnic groups from the latter half of the last decade (chart available in download).

Randall and Potter counties, where most of Amarillo metropolitan lies, offer an interesting perspective to what two neighboring communities look like.

Looking at just Amarillo, it is on par with the rest of the state in several ways: One in every four people is under the age of 18, nearly one in five people under the age of 65 is without health insurance and about 15% of the population is in poverty.

When we zoom out and look at the more rural communities these numbers shift away from the state percentages, including educational attainment and access to broadband, among other things.

But we know investment in all Texans is crucial to the success of the region and the state.

Only about 20% of the Panhandle population has completed post-secondary education with only one in three having some college courses under their belt.

Only about 20% of the Panhandle population has completed post-secondary education with only one in three having some college courses under their belt.

The Panhandle Workforce Development Board is working with area community colleges and high schools to provide more certifications and training to develop a workforce ready for a more diversified economy.

For those seeking education beyond that, West Texas A&M University is close by, just south of Amarillo.

Regardless of location, though, everyone in the Panhandle should have access to continuing education — or primary education for that matter.

According to Connected Nation data from Dec. 2020, 14 counties in the region have less than 50% availability of broadband service at the newly proposed speeds by the FCC of 100 megabits per second download and10 megabits per second upload.

This essentially means too many folks in the Panhandle, particularly in the rural areas, are lacking high-speed internet for work, school, telehealth and more.

As the Panhandle looks to attract more people and strengthen its current appeal, necessities like improved infrastructure—including broadband—will be key to its success.

Late last year, the City of Amarillo announced its partnership with Impact Broadband and Mimosa by Airspan for project Amarillo Connected, which aims to provide low-cost broadband to Amarillo and help up to 10,000 students and low-income residents.

Efforts like these showcase how that the area is already well positioned to tackle some of the challenges ahead thanks to an established regionalization approach.