The case for addressing wandering officers after Uvalde

Update (Feb. 28, 2023): After the publication of this blog, Uvalde CISD filed for a rehearing last week in an attempt to overturn the default upgrade in Arredondo’s discharge status. The first motion was filed on Feb. 24, and a second motion was filed Feb. 27.

For Texas to be the best place to live and work, public safety, which is predicated on trust in law enforcement, is critical. As Texas 2036 has previously described, the regulation of law enforcement in Texas is at a crossroads.

For the second consecutive legislative session, the 88th Legislature is considering recommendations for re-thinking the role of the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement, or TCOLE.

The findings and recommendations from the Sunset Commission — the group which reviews the need for and performance of state agencies — on TCOLE covered a number of issues, but the primary finding in the report on the agency was that the regulation of law enforcement in Texas “is, by and large, toothless.”

In addition to TCOLE and Sunset driving conversations surrounding Texas law enforcement this legislative session, few events loom larger than the tragic shooting at Robb Elementary in Uvalde and the actions of responding law enforcement.

One focal point of the immediate response and aftermath has been on the now-former Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District Chief of Police Pete Arredondo, who was fired by the CISD school board in August of 2022 with a less-than-honorable discharge.

Last month, Arredondo had his less-than-honorable discharge upgraded by default. Confidentiality rules shroud the specifics, but working through how this happened underscores the problems of what Texas 2036 has previously described as a “broken” system for handling less-than-honorable discharges, which sometimes lead to wandering officers.

Existing laws perpetuate the wandering officer problem

Anytime a peace officer leaves a law enforcement agency for any reason, the agency has to file an F-5 employment termination report to TCOLE. On the form, the agency checks one of three boxes —“honorable,” “general” or “dishonorable” discharge — to describe how an officer separated. It’s similar to the U.S. military’s process.

If an officer receives a less-than-honorable discharge, either general or dishonorable, they can appeal by filing a petition with TCOLE to receive a different discharge status on the F-5 form. If the officer wins the appeal, the F-5 is changed to show a new, upgraded discharge status.

However, just like a civil lawsuit, the officer wins by default if the agency that discharged the officer does not respond or participate in the hearing. Data obtained by Texas 2036 showed that almost 60% of the discharge upgrades that occurred in 2021 were by default, with the firing law enforcement agency not appearing.

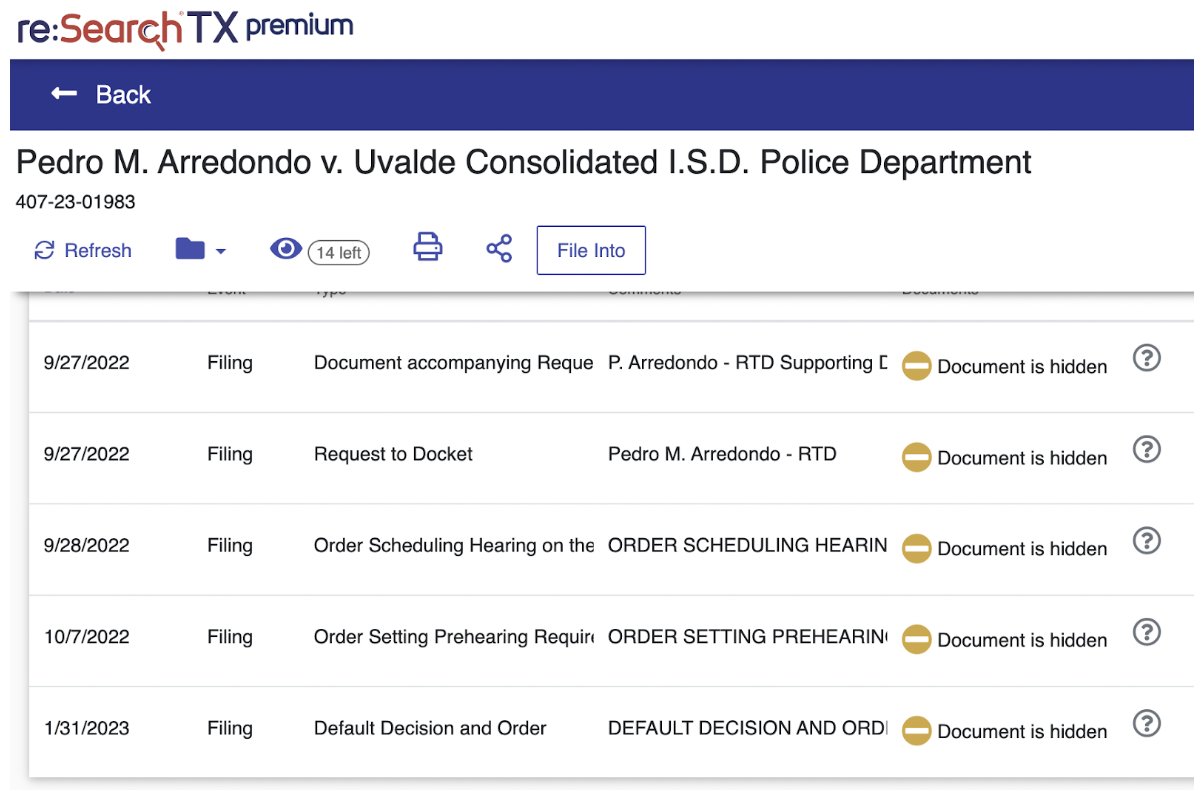

With limited publicly-available information, we don’t know much about Arredondo’s F-5 appeals process. What we do know is:

- He was fired on Aug. 24, 2022, and given either a “general” or “dishonorable” discharge;

- On Sep. 27, 2022, he appealed the classification of his discharge;

- Under Sec. 1701.4525, Occupations Code and other regulations, the law enforcement agency is responsible for defending the initial discharge determination in an F-5 appeal — in this case Uvalde CISD Police Department; and,

- On Jan. 31, 2023, a default judgment was entered in favor of Arredondo due to Uvalde CISD’s failure to respond, which will result in his discharge status being upgraded to either “honorable” or “general”

The underlying motivation for the F-5 system

The F-5 system was established to address the problem of wandering officers — peace officers who are fired from one agency and then find work at another. In theory, a general or dishonorable discharge was supposed to serve as a red flag for a hiring agency. In practice, it’s a red flag that doesn’t work.

The discharge categories are overbroad, the appeals too often lead to default upgrades, and confidentiality shields everything from scrutiny. A significant part of the Texas Law Enforcement Data Landscape released by Texas 2036 last November was dedicated to how the F-5 system not only fails to adequately address the problem but, in some cases, facilitates an officer’s wandering to other agencies.

Texas has over 2,700 law enforcement agencies, all with different standards for how key personnel records are kept and ultimately shared with hiring agencies. While legislation passed in 2021 goes a long way by requiring records sharing between agencies, there are still informational gaps by virtue of the number of agencies in the state.

To handle wandering officers, policymakers at a minimum have to focus on what happens at two critical points: what an agency does when an officer leaves and what an agency does before an officer is hired. The Data Landscape report recommended a number of improvements to the current system at both points. Here are four recommendations that represent a good start.

1. Replace the ill-defined discharge categories on the current F-5 report with neutral, descriptive reasons for separation.

A dishonorable discharge can be for anything ranging from criminal misconduct to insubordinate back talk. Moving towards neutral and basic reasons for separation will spare officers from an overly broad black mark and agencies from a non-useful indicator of past conduct. Simply abolishing any reason for separation — a current recommendation in the Sunset process — would provide even less information and transparency on wandering officers.

2. Ensure that all law enforcement agencies maintain detailed personnel records.

Texas has more law enforcement agencies than any other state, often attached to many kinds of entities – school districts, airports, private hospitals – all with different standards for how they record personnel events, commendations and discipline. The quality of a hiring agency’s background check is only as good as the personnel information maintained by the firing agency.

3. Ensure that the information on the report is available to the public.

In Arredondo’s case, the only thing we can infer is that the F-5 filed by Uvalde CISD indicated a less-than-honorable discharge. We don’t know whether it was a general or a dishonorable discharge, and we don’t know whether the default order left him with an honorable or general discharge. Ensuring that the information is public will let policymakers and stakeholders alike better monitor agency practices surrounding officer separations.

4. Require agencies to check a national law enforcement database before hiring.

The Data Landscape report identified hundreds of officers who started their policing careers outside of Texas law enforcement agencies. As more and more people move to our state, resources like the National Decertification Index provide an extra assurance that officers with a checkered work history do not bring them to Texas law enforcement without notice.

Arredondo’s case is yet another reminder that the F-5 system does not meet the public’s needs. Most Texans trust their local law enforcement to handle issues of public safety, trust that can easily be shaken and tarnished by a few who do not uphold the high standards the profession demands. The Texas Legislature has an opportunity this session to improve safeguards against officers who move between agencies due to poor performance, strengthen the profession, and better protect all Texans.