Across the state’s op-ed pages, education leaders and advocates have expressed significant frustration with the fact that the state has not released $18 billion in federal stimulus dollars to school districts. They’re not wrong: the pandemic has had a disproportionately negative impact on many low-income Texas students, and the smart use of federal resources will be arguably the most important tool for helping these young Texans catch up and achieve their full academic potential.

Time is of the essence. As school districts try to plan for additional learning time over the summer to help these kids catch up, they’re keenly aware that efficient use of funding takes time – time for planning, hiring, and curriculum development – while throwing together programs at the last minute can often be more costly and less effective for students.

And these efforts are essential. Earlier this year, the Texas Education Agency reported that optional beginning-of-year assessments found that only 29% of Texas 3rd graders achieved “meets grade level” in reading. Only 15% of Texas 4th graders achieved “meets grade level” in math. And only 12% of Texas 5th graders achieved “meets grade level” in science. With learning loss concerns shared across the political spectrum, swift deployment of financial resources for additional learning time, improved curriculum, and teacher training is vital.

So why isn’t the money moving? As with most bureaucratic and budgetary questions, there’s no one simple answer. Rather, a series of legal, financial, and historical barriers have placed Texas in a unique position, unable to deploy these funds without additional federal blessings. But the biggest reason may be an unexpected one: Texas spent so much new money on education in House Bill 3 – a much-needed investment that Legislators remain rightly proud of – that the federal spending equations risk producing some unintended outcomes.

Let’s break this down. Texas has received three tranches of federal stimulus funding for education:

- The CARES Act, passed in March 2020, had $1.29 billion for Texas in the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER I). These funds were largely used to finance a “hold harmless” for school districts, ensuring that school districts were fully funded based on initial state appropriations estimates from 2019 despite significant declines in student enrollment in 2020.

- The Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSA), passed in December 2020, had another $5.53 billion for Texas schools in the ESSER II Fund. These funds are the most frequently cited as needing to get spent as quickly as possible, though the state technically has until January 2022 before it is required to distribute to school districts and until September 30, 2022 before the funds must be obligated.

- The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), passed in March 2021, had yet another $12.42 billion for Texas schools. To “the extent practicable,” the state is implored to release these funds to school districts within 60 days of the bill’s March 11 enactment, but the funds are only reallocated to other states if not used within a year (“A State shall return to the Secretary any funds received under this section that the State does not award within 1 year of receiving such funds and the Secretary shall reallocate such funds to the remaining States[.]”) The state and school districts then have until September 30, 2023 before the funds must be obligated. In state budget terms, that’s fiscal year 2024 – meaning that the budget writers in the 2023 session could have theoretical access to some of these funds if they remain unspent.

ESSER II and ESSER III combined provide $18 billion in resources to the Texas legislature to aggressively tackle learning loss and make related educational improvements. But, as always with 600-page bills, there are details to sort through.

With ESSER II, a unique “proportional maintenance of effort” clause – designed to prevent state budget cuts – began to create issues for the state. Basically, what this does is require the state to maintain the percentage share of its overall budget dedicated to both PK-12 and higher education – calculated separately – over the next few years. However, the lookback period used (FY 2017, 2018, and 2019) to calculate the state’s baseline falls squarely before the implementation of House Bill 3, which massively increased state spending on education. So, even though spending on higher education is slated to slightly increase going forward, it is not increasing at a rate fast enough to maintain its pre-HB 3 budget percentage.

| CRRSA Section 317: (a) At the time of award of funds to carry out sections 312 [Governor’s Emergency Education Relief (GEER) Fund] or 313 [ESSER II] of this title, a State shall provide assurances that such State will maintain support for elementary and secondary education, and for higher education (which shall include State funding to institutions of higher education and state need-based financial aid, and shall not include support for capital projects or for research and development or tuition and fees paid by students) in fiscal year 2022 at least at the proportional levels of such State’s support for elementary and secondary education and for higher education relative to such State’s overall spending, averaged over fiscal years 2017, 2018, and 2019.

(b) The Secretary may waive the requirement in subsection (a) for the purpose of relieving fiscal burdens on States that have experienced a precipitous decline in financial resources. |

Similar language exists in ESSER III, with the same lookback years and the addition of FY 2023 proportional budget requirements.

| ARPA SEC. 2004(a): STATE MAINTENANCE OF EFFORT.—

(1) IN GENERAL.—As a condition of receiving funds under section 2001, a State shall maintain support for elementary and secondary education, and for higher education (which shall include State funding to institutions of higher education and State need-based financial aid, and shall not include support for capital projects or for research and development or tuition and fees paid by students), in each of fiscal years 2022 and 2023 at least at the proportional levels of such State’s support for elementary and secondary education and for higher education relative to such State’s overall spending, averaged over fiscal years 2017, 2018, and 2019.

(2) WAIVER.—For the purpose of relieving fiscal burdens incurred by States in preventing, preparing for, and responding to the coronavirus, the Secretary of Education may waive any maintenance of effort requirements associated with the Education Stabilization Fund. |

Confusing enough? Let’s break it down some rough numbers. For this analysis, we’re going to use biennial appropriated funding rather than actual annual expenditures, and we aren’t going to adjust for capital projects, research, or other potentially non-allowable costs. Forgive us. It’s complicated, and we’d like to show the math. These numbers look at state funds (general revenue, general revenue-dedicated, and other funds) and exclude federal funds.

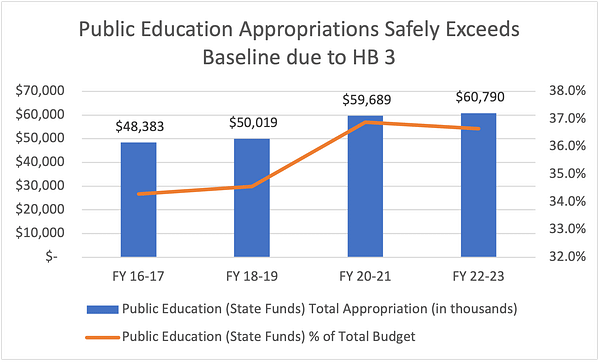

As shown below, state spending on public education in our proxy baseline biennia (FY 16-17 and FY 18-19) is significantly below state spending on public education after the passage of HB 3. Both the total dollars spent and the percentage that public education fills of the state budget are noticeably larger in FY 22-23 than in FY 16-19.

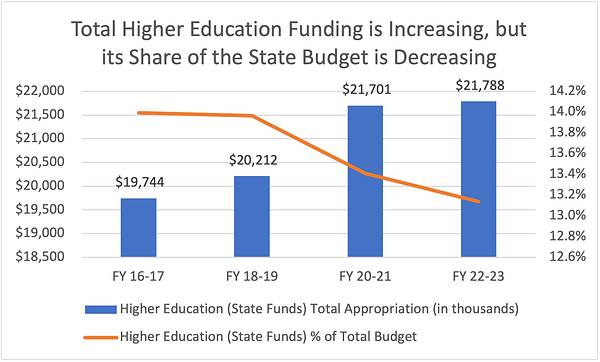

As shown below, state spending on higher education runs into a much quirkier and problematic outcome. While overall higher education spending has increased by about 10% over the 4 biennia displayed, the rate of growth for the budget as a whole (about 15%) outpaces the growth of spending in higher education. The declining orange line in the chart below threatens the state’s ability to certify that it can comply with ESSER II and ESSER III requirements.

So why is the orange line for higher education declining so precipitously despite increased higher education spending? Simply put, the cost of HB 3 – the massive infusion of state resources into public education – caused the denominator of state spending to grow at a disproportionate rate. Coupled with rising health care costs consuming a greater chunk of the pie, higher education funding simply hasn’t kept up.

Yesterday, the federal Department of Education released extensive guidelines to provide states flexibility in how they can calculate and certify compliance with these maintenance of effort requirements. With this new flexibility, the state may be able to find a way to get the money moving within its budgetary constraints — or it may still need to seek a waiver. If a waiver is necessitated, Monday’s guidance provides the state with the process to do so and a path to getting the money moving, albeit on a DC schedule rather than a Texas legislative calendar.