Student readiness: Data provides critical insights

Texas 2036 and the George W. Bush Institute explore student career readiness and its impacts on Texas’ future prosperity in their report “The State of Readiness: Are Texas students prepared for life after high school?” Here is a preview (read part I).

Data provides critical insights about readiness

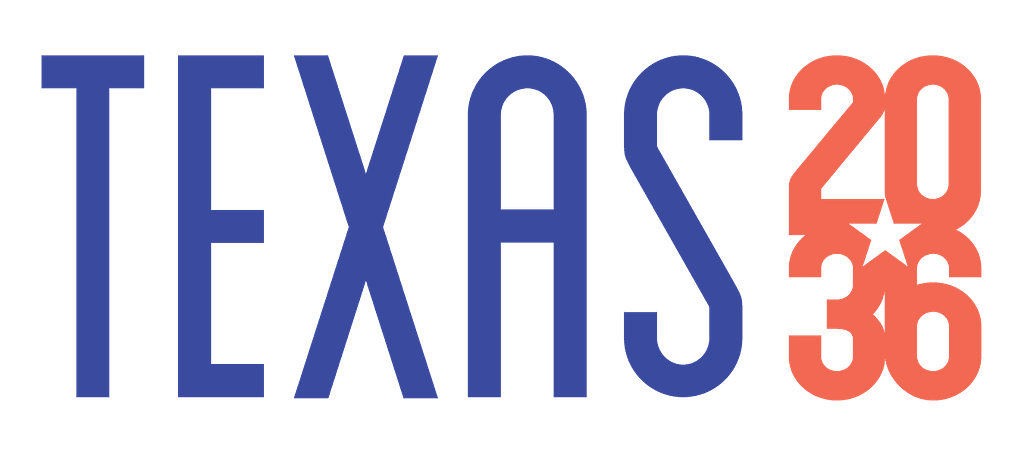

If Texas wants its students to be ready for life after high school it has to take readiness in the younger grades seriously. Advancing students who are not on grade level will produce high school seniors who are not academically ready for life as adults. Today, the rate of readiness of Texas students peaks in kindergarten at 58% (see chart below).

Texans know the readiness rates of students across grade levels because Texas is deeply committed to collecting data and measuring student outcomes. In Texas, we measure the performance of every student and hold school districts accountable for those results because every student – no matter their race or income – matters.

Texas is able to report to parents the academic performance of every child on a yearly basis and provide information on academic outcomes at the campus, district, and statewide levels. Data indicate which students are on track and who is falling behind – and we can break out that data by race, ethnicity, gender, and ability, allowing state and education leaders to identify and address equity issues.

Texas has several indicators that inform parents and policymakers whether students are on track for life after high school, including:

- the number of students who graduate high school prepared for college, a career or the military; and

- student performance in four core subjects: reading, math, science and social studies as measured by the State of Texas Assessment of Academic Readiness (STAAR).

We can then compare these results with the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), often called “The Nation’s Report Card,” and other national exams to measure the readiness of Texas students relative to their peers in other states.

The data provided by these tools and indicators provide the basis for the academic accountability system (known as the A-F system), which measures the performance of Texas schools and school systems in ensuring student readiness.

The data provided by state and national assessments, along with Texas’ academic accountability system, provide parents and caregivers with timely and actionable information about their child’s educational progress. An analysis of statewide student performance provides policymakers with critical insights that guide the development of policies that address equity issues, improve student outcomes, and effectively and efficiently allocate taxpayer resources.

To understand and diagnose the issues in Texas’ readiness, Texas has to commit to measuring student and district performance. Good policy is not possible without it.

Just as regular medical check-ups are necessary to prevent adverse health outcomes – and identify the correct treatment when something unexpected shows up – regularly measuring student performance is essential to promoting healthy student outcomes and readiness. Ignoring student performance risks allowing students to fall behind while much-needed resources and interventions remain un-utilized.

But not all tests provide the data necessary to accurately, transparently and fairly measure student readiness. While national tests like NAEP and the SAT provide important context for Texas student performance, they do not measure individual student performance against Texas’ academic standards.

The only truly transparent and accurate measures of an individual student’s performance on state standards are annual state assessments in core subjects.

Annual tests in reading and math along with regular check-ups on science and social studies let educators know whether students are on track to be ready for adult life. Because every student in Texas takes the same exam, we can compare districts and schools to each other. Without state assessments, student progress is measured in averages and anecdotes. With them, we have clarity and transparency for families.

The academic accountability system allows the state to hold school districts accountable for how well they are preparing their students for life after high school and allows the state to intervene when a school system is chronically unable to academically equip students.

Without the information from the apples-to-apples comparison from the accountability system, Texas parents, students, and taxpayers would have no objective information on how their school district or campus is performing.

Data helped Texas officials make smart policy before

In the 1970s, data showed trends similar to those Texas is seeing today: students were not being prepared for life after high school. Survey data found that two-thirds of Texans with Spanish surnames were so academically unprepared that they were unable to function in society. SAT scores were in decline across demographic groups, with the average national score falling over 40 points from 1966 to 1980 on the SAT reading section.

Starting in the mid-1980s, Texas led the way nationally on two key bipartisan efforts to improve student outcomes: standards-based reform and student data disaggregated by demographics including race, gender, and income. Texas began by establishing clear standards for what students should learn in each grade (referred to now as the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills, or TEKS), then developed a statewide test to determine whether or not students learned the material associated with that grade standard.

For the first time, students were measured against specific benchmarks, and that performance was reported to the state.

Expectations were consistent, transparent, and rigorous for all students – a revolutionary concept. Test results were reported to the state and broken into groups by race, gender, and income. By the early 1990s, if a school district reported unacceptably and persistently low results, the state took action to improve the academic conditions of that school.

These efforts resulted in rapid improvements in student outcomes. Texas saw scores improve in core skills like using addition or subtraction – important mathematics concepts for all adults to understand – and scores continued to improve on subsequent assessments.

These efforts resulted in rapid improvements in student outcomes. Texas saw scores improve in core skills like using addition or subtraction – important mathematics concepts for all adults to understand – and scores continued to improve on subsequent assessments.

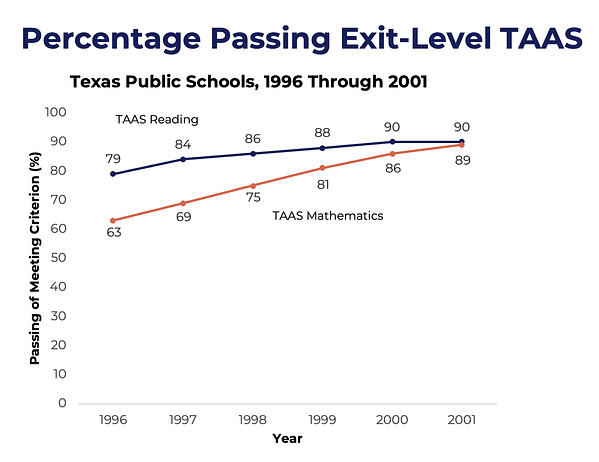

In 2001, 26% more students passed exit-level math tests and 11% more passed exit-level reading tests than they did in 1996 (see chart). These results were confirmed by Texas’ performance on the NAEP.

When standards slip, students suffer

Sadly, over time, Texas weakened its approach and lowered standards for its public education system, removing and relaxing passage requirements for lower grades and requiring high schoolers to pass fewer exit-level tests for high school graduation.

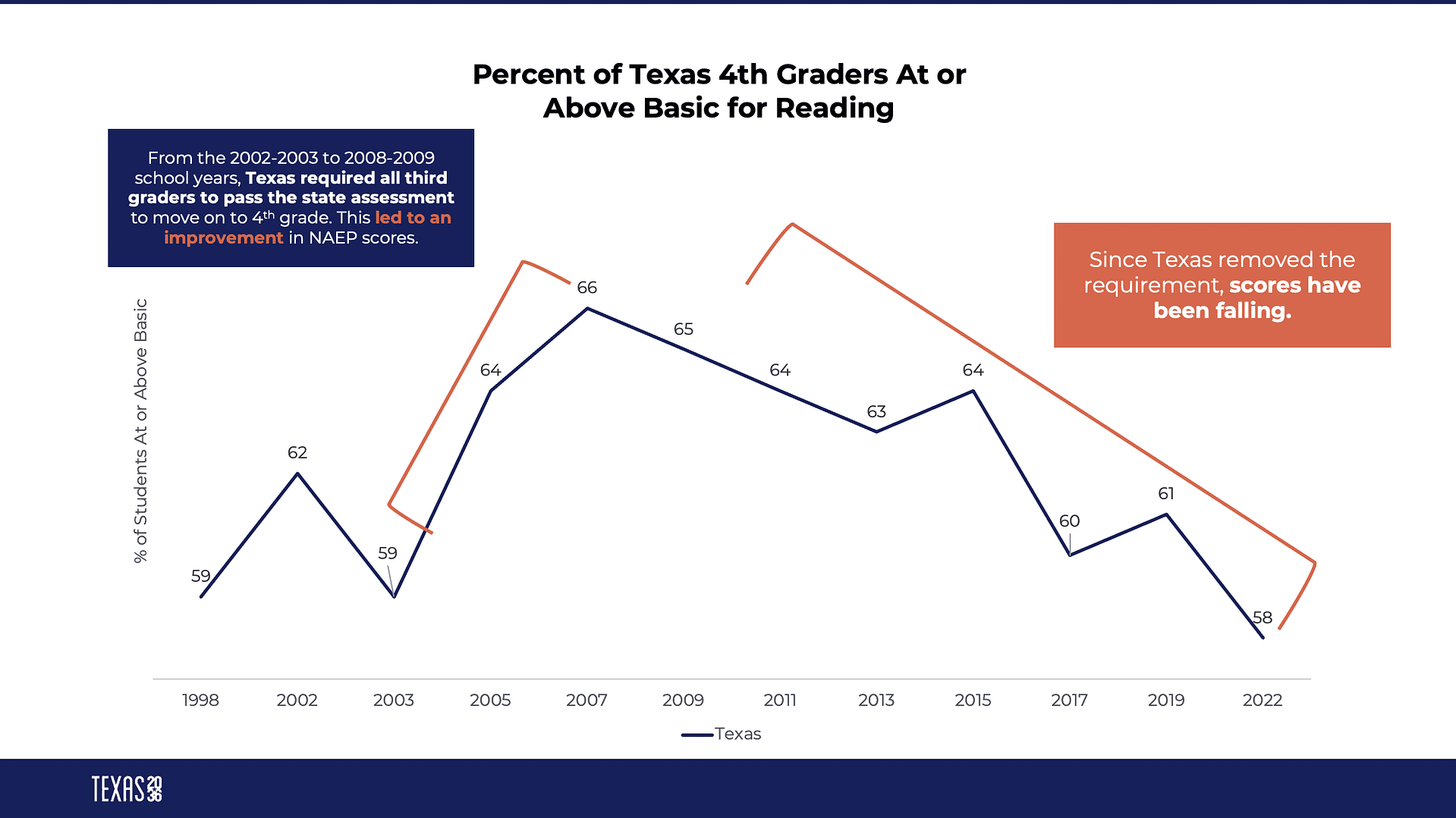

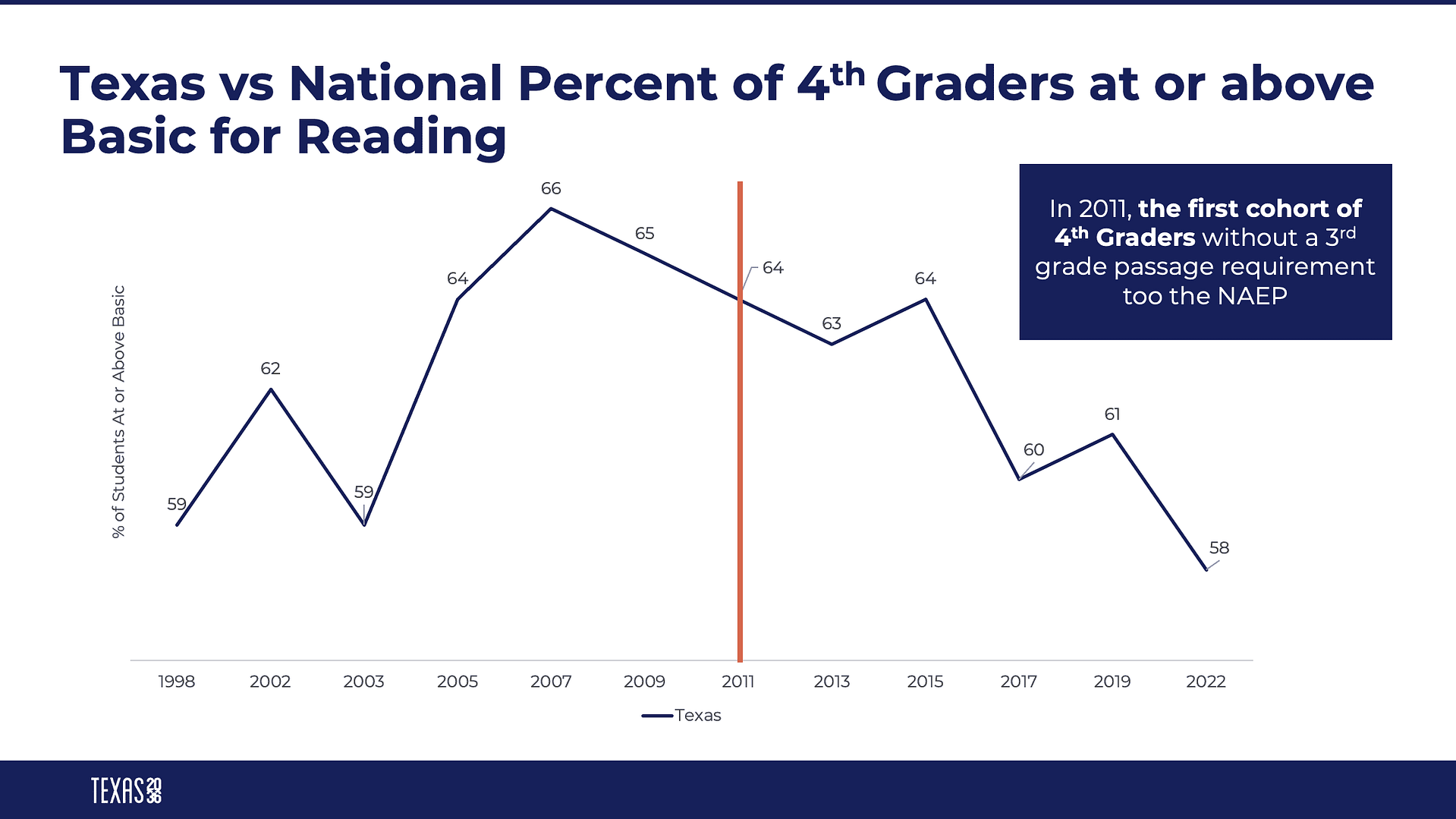

From the 2002-2003 to 2008-2009 school years, Texas required students to pass the third-grade reading exam to advance to fourth-grade. Over that time, Texas scores in fourth-grade reading saw a six-point increase in the percentage of students at the Basic level on the NAEP.

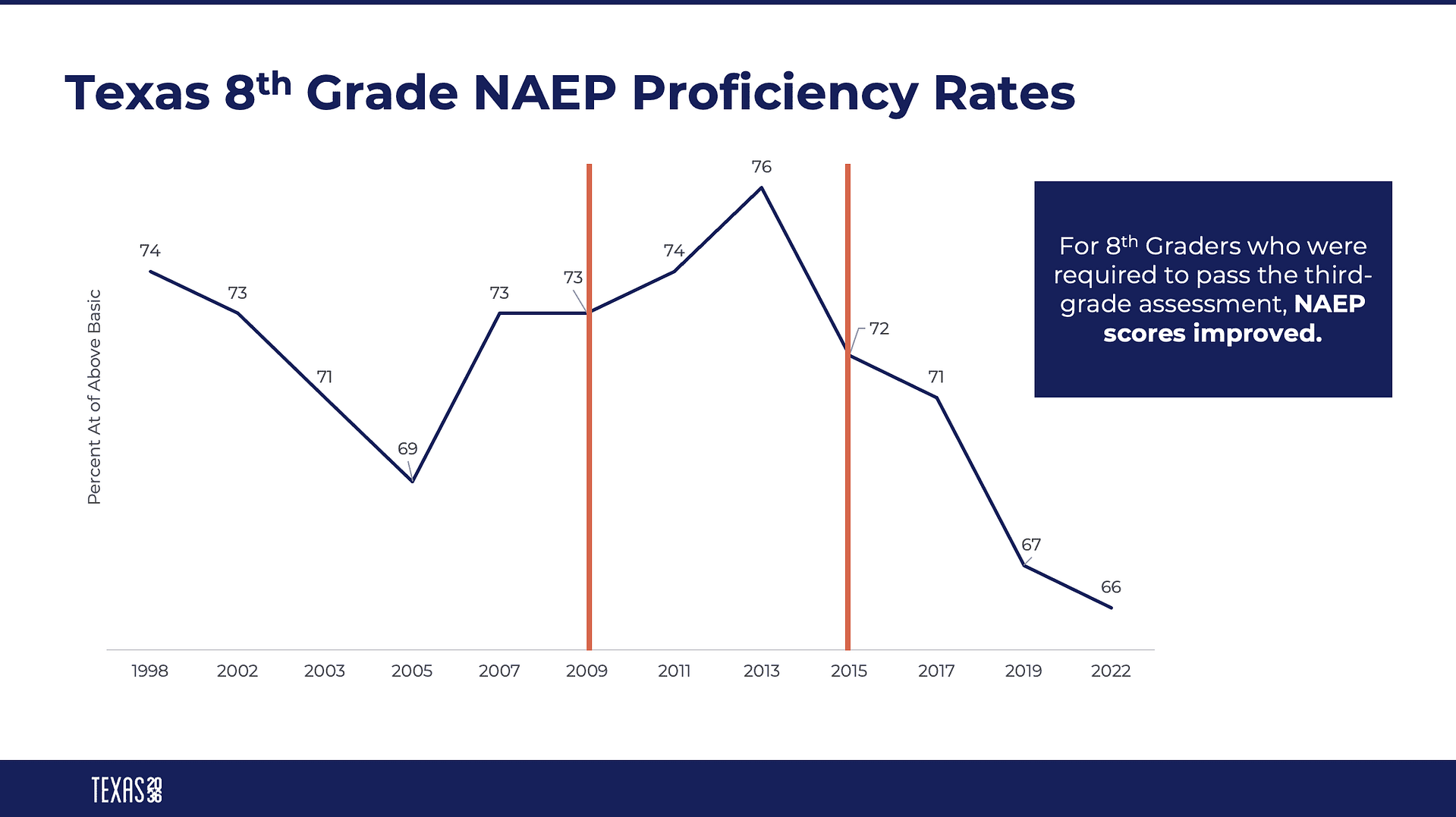

By 2009, Texas removed the third-grade passage requirement, which preceded a collapse in NAEP fourth-grade reading scores. Subsequent eighth-grade NAEP reading scores showed a decline in both basic and proficient readers beginning in 2013-2014 – the exact year that the first cohort without a third-grade passage requirement was in eighth-grade – and eighth-grade reading scores have been in decline ever since.

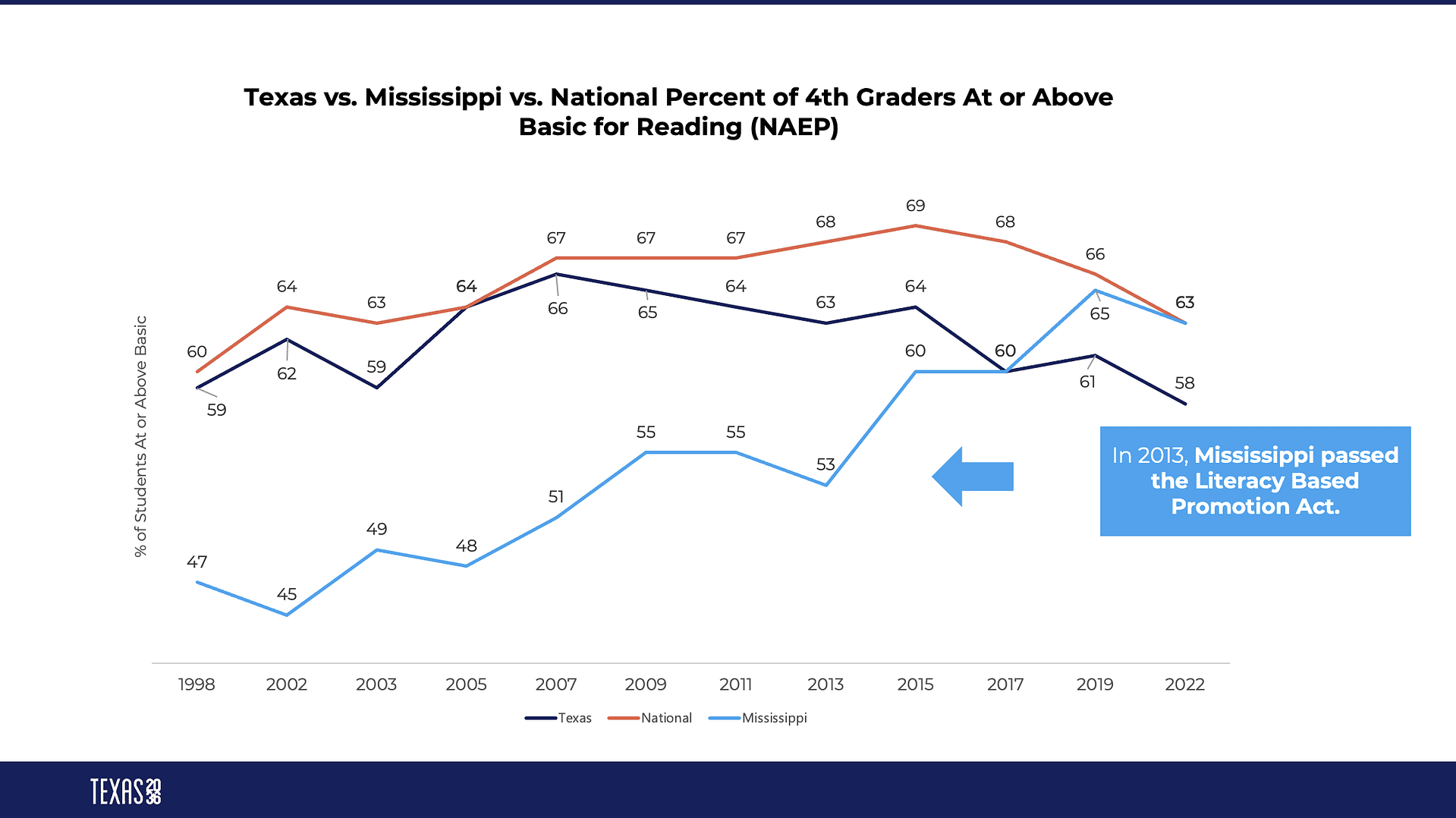

Over the same period, Mississippi increased its standards and required students to pass their third-grade reading assessment to move on to the next grade. As Texas’ scores collapsed, Mississippi increased reading scores by over 20%, surpassing Texas and the national average scores.

It is worth noting that the cause of this decline has been the subject of speculation over the years. Some education advocates have suggested that the decline in Texas school performance is related to state budget cuts that went into effect for the 2011-2012 school year, but fourth-grade scores had been declining for five years prior to these cuts.

Another theory behind this decline related to textbook quality has been proposed. Around the 2010s, Texas changed its curriculum requirements, allowing districts to buy non-state approved curricula. Some posit this caused the score decline. It could be that the confluence of the removal of the third-grade passage requirement coupled with the decline in curricular quality worked together to drive down scores.

While more research is needed to understand this decline, it is clear that the solution that Mississippi implemented to raise reading scores is working significantly better than Texas’ approach over the past several years.

Using data & collaboration to improve readiness

Developing effective efforts to improve educational outcomes for Texas students requires the guidance of timely and reliable data. The quantity and quality of available data can be expanded and improved through inter-agency collaboration and data sharing, as evidenced by the Tri-Agency Workforce Initiative. This data can, and should, be used to improve the state’s Industry Based Certification list.

In 2021, House Bill 3767 (87R) formalized in statute the Tri-Agency Workforce Initiative (Tri-Agency), an effort begun by Governor Abbott in 2016 to improve collaboration among the Texas Education Agency, Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board and Texas Workforce Commission.

The commissioner of each of these agencies oversees state databases that house data related to workforce development goals by the three agencies; however, these are not interagency databases, which prevented ready access across the three agencies. HB 3767 removed interagency barriers by formalizing in statute the Tri-Agency partnership and set goals for the state’s education and workforce systems.

Through the Tri-Agency’s work towards “[designing] an integrated educational and workforce data infrastructure with a shared data governance policy,” the TEA is able to access data necessary to determine whether adopted readiness indicators are resulting in improved college and career outcomes for Texas students.

The Tri-Agency is also creating “publicly available and user-friendly data dashboards that report education and workforce outcomes data aligned to Tri-Agency priorities and disaggregated by income, race, ethnicity, gender, and region.” This level of transparency will help empower Texas parents and students to plan their education and career paths by showing available options with the greatest indicators of success best aligned with students’ career goals.

One of the most common paths students take toward career readiness is the Industry-Based Certification (IBC). Texas has seen a considerable increase in the number of IBCs received by students – a 13 percentage point increase since 2018 – making this the fastest growing of the primary CCMR indicators.

As Texas seeks to improve readiness, it should invest in high-quality pathways that increase career readiness. IBCs offer a good course forward toward addressing Texas’ readiness needs if they provide students with a certification that can lead to a job.

A strong approach to IBCs requires that:

- IBCs are aligned with employer needs. For IBCs to have any real value to students, they must certify competency in marketable, in-demand skills.

- IBCs indicate a mastery of skills. Possession of an IBC should indicate that a student has successfully mastered the knowledge and skills required by an industry or occupation.

Alignment between IBCs and the labor market matters – without it, young people are set up to fail, holding valueless credentials. For example, in the 2021-2022 school year, 46,552 students were enrolled in a floral design class. 3,759 of those students were enrolled in an advanced floral design course.

However, labor market projections indicate that there will only be 41 total available floral designer jobs per year in Texas for the next decade. Texas will designate many of those floral design students as career-ready – but the students will likely struggle to find a related job given the mismatch of supply and demand.

IBCs should also indicate a mastery of skills. This means that the student should have the appropriate amount of coursework, on-the-ground training options, and rigorous certification pathways that help to demonstrate mastery. A certification should be a capstone in an aligned series of courses that all work toward a high-wage and high-demand job.

Texas is working to make sure that students who receive an IBC do so at the end of a rigorous series of courses that relate to that certification. This work, taking place through the TEA rules process, is important to ensuring student readiness and should be continued over the next several years.

Ultimately, the type of seamless, interagency data access advanced by the Tri-Agency Workforce Initiative is particularly useful for strengthening the IBC list and ensuring it is aligned with employer needs and productive pathways toward college or career readiness. Higher education data allow TEA to monitor whether courses are helping students identify and qualify for postsecondary education opportunities in addition to providing them with in-demand skills.

Simultaneously, labor market data helps ensure that IBC programs are resulting in career success for students both in terms of higher rates of job attainment and better wage premiums. The three agencies are working together to tell parents, students, and taxpayers whether the current system of college, career, and military readiness in Texas K-12 schools is actually resulting in more graduates ready for life after high school.