Here’s a frequent question I get from Texans about health care and health insurance: “How has the pandemic impacted our uninsured rate?”

The answer is … it’s complicated.

Here at Texas 2036, we always start with examining the data – and the data on this is all over the place1:

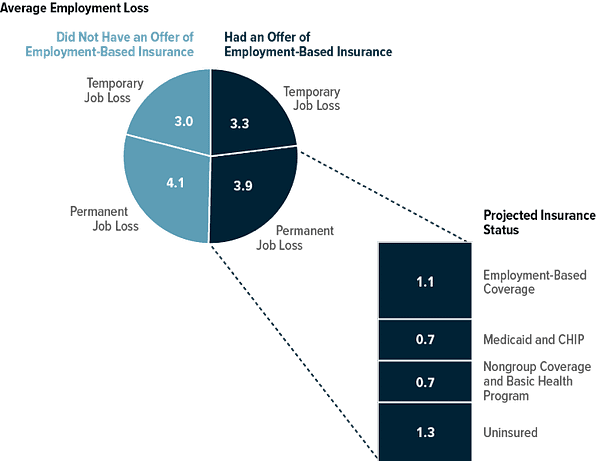

- In May, the Kaiser Family Foundation estimated that 26.8 million Americans had lost employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) due to pandemic-related job loss, including 1.6 million Texans.

- Families USA released a study (also in May) putting the nationwide number at 5.4 million people, and the Texas total at 659,000.

- Then the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) issued a report in September estimating 1.3 million people nationwide would permanently lose job-related insurance coverage. That report did not have state-specific breakdowns.

After all of that, the Kaiser Family Foundation updated their estimates this month, concluding:

“While much is unknown, a review of administrative data suggest that the uninsured rate may not have changed much during the pandemic to date.”

Their updated analysis makes the following points:

- Overall loss of Employer-Sponsored Insurance was not as dire as projected, because job losses were concentrated in industries less likely to offer Employer-Sponsored Insurance to begin with;

- Enrollment in alternative forms of insurance, such as Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act Marketplace, has increased; and

- Employment rates are recovering.

It’s hard to say how Texas fares by this methodology (the latest report lacked state-specific analyses). Texas has not expanded Medicaid, so while the Texas Medicaid caseload in September had increased about 12%, or 473,589, from the same time last year, the absolute growth in Texas Medicaid enrollees may be lower than in states that have expanded Medicaid eligibility.

- A deeper dive into these Texas Medicaid numbers shows that children’s Medicaid (which is Texas’ largest Medicaid program) had the greatest absolute increase, going from 2,830,309 to 3,196,284, an increase of 365,975 (13%). Pregnant women had the highest relative increase in Medicaid enrollment, increasing from 140,014 to 217,074, which represents an increase of about 55% (77,060).

- The Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) offers low-cost health coverage for children from birth through age 18. CHIP is designed for families who earn too much money to qualify for Medicaid but cannot afford to buy private health coverage. For September 2019-September 2020, the number of enrolled children in CHIP dropped about 16% from 361,667 to 303,818.

In addition, Texas has seen a surge in enrollment on the Affordable Care Act Marketplace. In the open enrollment period that just recently ended, signups on HealthCare.gov in Texas were about 15% higher than last year. Compared to the 35 other states utilizing the Federal Exchange, that is the highest percentage increase.

There are a number of possible explanations for such a dramatic increase in signups, including that more people might have needed insurance after losing a job; more Texans might have decided to get insurance after seeing the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic; and/or there has been greater awareness in recent months about the availability of coverage. Unfortunately, we don’t have good enough data to say how each might have affected signups.

There’s also some question about whether lower net premiums might have led more people to sign up for coverage — we may have more insight into that with additional federal data in coming months.

One way or another, it’s clear that the data is trying to tell us something — about how the pandemic affected health care coverage and access in Texas, and how Texans responded to it. We’ll remain vigilant on updated figures as we work to answer the ultimate health care question: how do we ensure that all Texans have access to affordable health care?

1 It’s important to note that these numbers are not apples-to-apples. These studies are measuring slightly different things. For example, the Kaiser estimate was measuring the total number of people who had lost employer-sponsored insurance, without measuring how many of those individuals would subsequently sign up for other insurance available to them. On the other hand, the Congressional Budget Office report estimated the number of people who had lost employer-sponsored insurance and would remain uninsured through the end of the year.