There is an alarming lack of data in our civil and criminal justice systems nationwide—and Texas is no exception. Data reporting from state courts present an incomplete picture of our third branch of government and its central role in the delivery of justice. Not only does this incomplete data limit us to the broadest view of the court backlog issue in Texas, but it also obscures both the work of individual courts and important trends in how certain kinds of cases are decided.

Statewide figures show the high-level impact of the pandemic and the ongoing efforts to address the backlog. Data provided by the Office of Court Administration, or OCA, indicate that there were 154,074 more pending cases in Texas district courts as of June 30, 2022 than there were on March 1, 2020 across civil, criminal, family, and juvenile case dockets. That is a modest improvement from the roughly 157,000 pending cases reported in a legislative hearing back in May 2022.

But even the most granular data reported to the state can’t give us adequate information about how long those cases have been pending, which courts have the largest caseloads, or even what kinds of cases are pending in many instances. So we know just enough to know that justice is being significantly delayed for many Texans, but we don’t know enough to fully comprehend the magnitude of the problems facing our justice system.

It’s harder to fix what we can’t yet measure.

As the Texas Legislature thinks about ways to help courts improve their backlogs and further reform our justice systems, it should be mindful about the data we need at all levels of the judiciary to sustain efforts beyond 2023. Current aggregate judicial data collected by the state has serious shortcomings. With the right investments, the data that the state collects and publishes from county, district and appellate courts can be an asset to justice-related policymaking as opposed to a mere byproduct of the judiciary.

At the center of these efforts are the Texas Judicial Council—the policymaking body for the judiciary—and OCA as the judiciary’s administrative agency. In recent years, the Council and OCA have offered reports and testimony highlighting the multiple constraints of the state’s aggregate county data collected from trial-level district and county courts.

First, the state’s aggregate data obscures what is happening in most individual trial courts across rural and urban Texas.

Calling the jurisdictional geography of our district courts complex is an understatement. For district courts in rural Texas that cover multiple counties with overlapping jurisdictions, data from any one county is an incomplete picture of a court’s total caseload. Where the case backlog is especially severe in more urban counties that can have dozens of district and county courts, the aggregate data conceals the exemplary, hard-working judges as well as those that may be less timely in working through cases on their dockets. The few instances where the state’s data actually reflects an individual district court’s docket are where the jurisdictional lines of one court happen to coincide with county lines in the right way.

Second, we don’t have information to accurately assess the kind of work judges have before them, much less how laws are applied in practice.

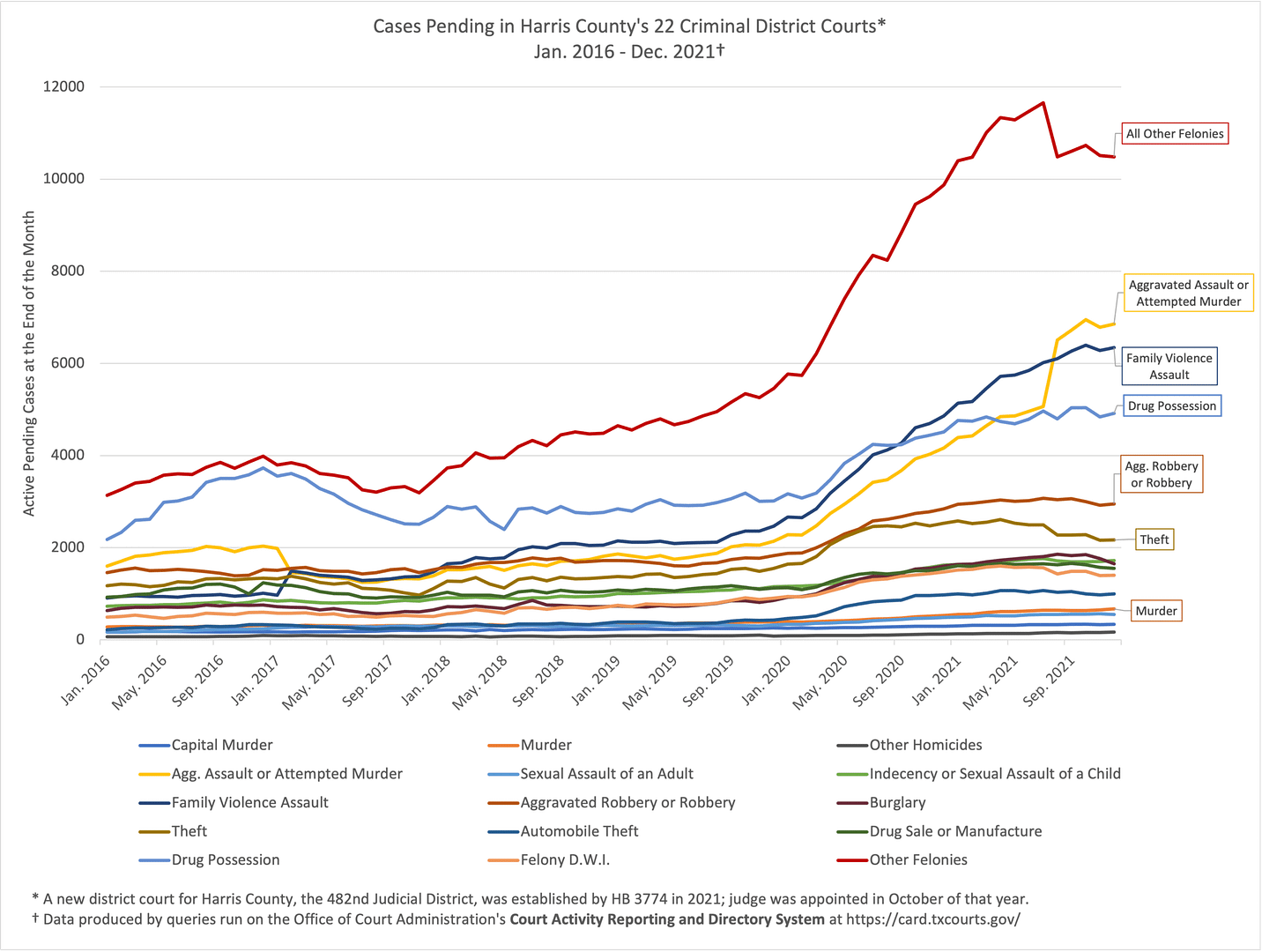

For example, district courts will report criminal cases in 15 high-level categories such as aggravated assault and drug possession — everything from marijuana to methamphetamine — and then report one “other felonies” category of cases that can account for a quarter of a county’s criminal docket.

Even where we can evaluate an individual court’s performance, we don’t have data to adequately describe the kind of work the court is doing. The data doesn’t distinguish between a complex, resource and time-intensive public corruption trial and an arson case that is resolved with a guilty plea, both of which are counted under “other felonies.”

In Harris County, “other felonies” were 26% of the district courts’ pending caseload in 2020. As the graph below shows, the vague “other felonies” have been driving the backlog of pending criminal cases in Harris more than any one case category. We can also see other aggregate data, such as the number of cases with a court appointed attorney or the number of jury selections, but those figures are disconnected from the categories of cases.

To replace aggregate reporting, the Judicial Council and OCA have called for the collection of case-level statistical data from our trial courts. This is data linked to individual cases that could produce figures incorporating multiple variables related to the case’s courts, type, timeline, management and outcome.

To replace aggregate reporting, the Judicial Council and OCA have called for the collection of case-level statistical data from our trial courts. This is data linked to individual cases that could produce figures incorporating multiple variables related to the case’s courts, type, timeline, management and outcome.

At the appellate level, the current judicial data picture only gets worse.

Data from the 14 state courts of appeals shows the number of criminal cases and the number of civil cases appealed from counties, with no further breakdown of the types of cases or the types of courts that are the source of the appeal. This means we don’t know how many criminal appeals are related to cases about violent offenses or drug-related offenses — we can’t even distinguish between juvenile and adult cases.

We likewise don’t know how many civil appeals arise out of family law disputes or contractual disputes. Far from having data that could conceivably link trial-level information to a subsequent appeal, we don’t capture data to describe the kinds of cases that are being appealed.

OCA has made two key funding requests ahead of the 2023 legislative session to make real progress on judicial data:

- A new data management system at OCA that is equipped to receive case-level data reported from trial courts

- A new case management system for the appellate courts that not only updates an outdated legacy system but could lay the groundwork for vastly improving appellate-level data reporting

In a near-prophetic observation almost a century ago, the first president of the Judicial Council said, “… to deal intelligently with the problems which will confront this Council it must first obtain complete data concerning the conditions in the Courts of Texas.” The same forward-thinking outlook should motivate these one-time, long-term investments in our judicial data infrastructure.